Seeds, Spores & Food – The Foundations of Regional Resilience

The Central Valley & The Willamette Valley: A Tale of Two Agricultural Futures

Why Cascadia Must Build a Regenerative Food & Seed System Now

1. Introduction: The Need for a Regenerative Cascadia Food & Seed System

Our modern food system is built on fragile foundations. For decades, the U.S. has relied on industrial-scale monoculture to feed its population, with California’s Central Valley serving as the backbone of fresh food production. However, the Central Valley—a region that supplies nearly 40% of the nation's fruits, nuts, and vegetables—is on the brink of collapse due to water shortages, climate extremes, and soil depletion.

As California’s agricultural heartland falters, Cascadia has a choice:

Do we continue to rely on a failing food system?

Or do we step up and create a regenerative, decentralized food network rooted in bioregional resilience?

This is not just a theoretical discussion—it’s an urgent necessity. The Willamette Valley, one of the most fertile agricultural regions in North America, has the potential to be a model for food sovereignty. But to achieve that, we must take action now—through seed-saving, regenerative farming, and a regional food infrastructure that can withstand future disruptions.

In this article, we will explore:

Why California’s Central Valley is facing an agricultural collapse.

How the Willamette Valley offers a sustainable alternative.

What steps we must take to build a resilient Cascadia Food Guild.

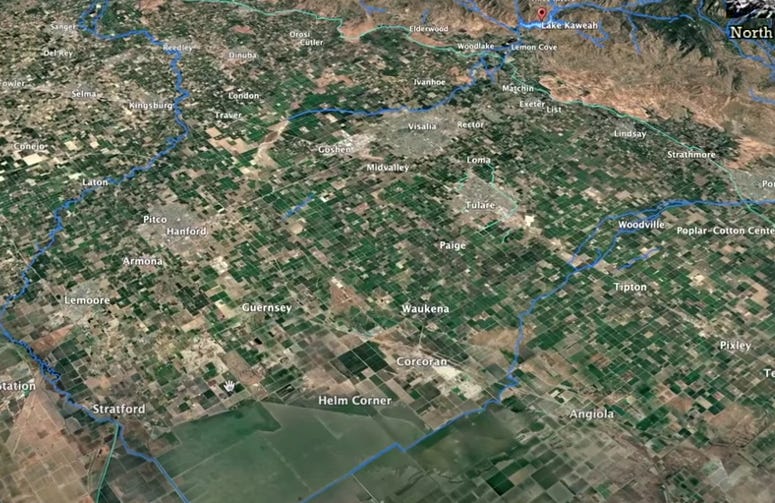

2. The Central Valley: An Agricultural Empire on the Brink

A Food Giant Built on Borrowed Water

California’s Central Valley is often called the “food basket” of the U.S., producing:

80% of the world’s almonds

99% of the U.S. walnuts, pistachios, and artichokes

One-third of the country’s tomatoes

Massive amounts of lettuce, grapes, citrus, and avocados

However, this productivity comes at a steep cost. The valley’s agriculture is heavily dependent on irrigation, drawing billions of gallons from the Colorado River and California’s over-pumped aquifers.

The Water Crisis: A Looming Disaster

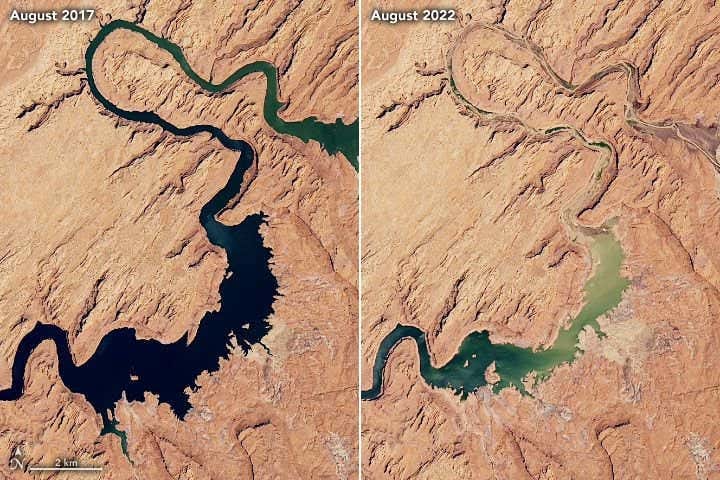

The Colorado River, once a reliable water source for farms, is now in severe decline due to:

Decades of overuse—more water is allocated than the river actually provides.

Mega-drought conditions—2020-2022 saw the worst drought in 1,200 years.

Collapsing reservoirs—Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the largest in the U.S., are at historic lows.

As a result, farmers are now losing water allocations, leading to:

Mass crop failures and land abandonment.

The destruction of almond and citrus orchards that took decades to establish.

A growing exodus of farmers selling their land to agribusiness corporations.

Even worse, in 2023, extreme flooding followed the drought—eroding topsoil, drowning crops, and causing billions in damage. Instead of replenishing groundwater, much of the floodwater washed away into the Pacific.

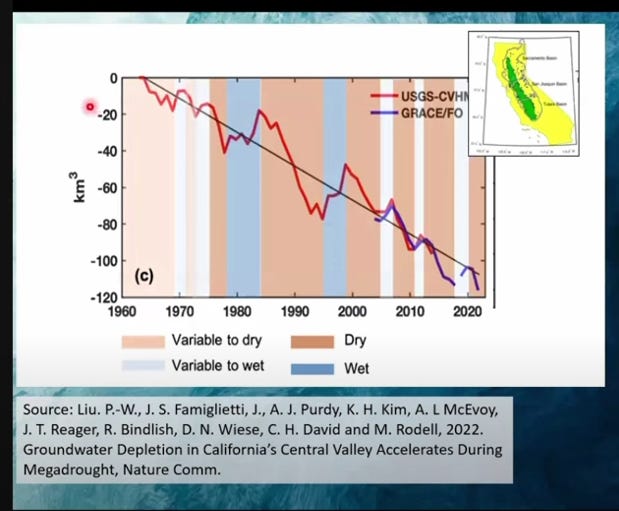

This is a graph of groundwater declines in California’s Central Valley over the years. There is a full video on water challenges, here.

It Gets Worse!

On January 31, 2025, the Trump administration directed the Army Corps of Engineers to increase water releases from reservoirs such as Lake Kaweah and Success Lake. The stated purpose was to maximize water supplies for firefighting efforts in Los Angeles. However, this decision raised concerns among local officials about potential flooding and the loss of irrigation water. After discussions, the planned releases were scaled back to mitigate these risks.

Critics have labeled this action as dangerous and unnecessary, pointing out that the released water would not effectively reach Los Angeles for firefighting purposes. Instead, it could lead to flooding in downstream communities and reduce water available for agriculture.

This event is part of a broader debate over water management in California, with differing perspectives on how to balance water distribution between environmental needs, agricultural demands, and urban requirements.

This is a great Youtube overview of this and other varied fiascos.

Industrial Farming’s Hidden Costs

Beyond water shortages, Central Valley agriculture suffers from:

Soil degradation – Overuse of synthetic fertilizers has depleted microbial life.

Salinization – Irrigation mismanagement has turned some farmland into salt flats.

Corporate Land Grabs – As small farms fail, major agribusinesses buy them up, consolidating food production into fewer hands.

The Central Valley is a cautionary tale—a region that once seemed unstoppable is now crumbling under the weight of its own excesses.

3. The Willamette Valley: A Model for Resilient Agriculture

Why Cascadia is Different

The Willamette Valley, stretching from Eugene to Portland, is one of the most diverse and fertile bioregions in North America. Unlike the Central Valley, it:

✅ Receives reliable rainfall (even during dry years).

✅ Has naturally rich soils built from volcanic activity and river deposits.

✅ Supports a wide range of crops—over 200 different varieties can thrive here.

✅ Has a history of diversified farming (before globalization shifted it toward monoculture).

Even in the fertile Willamette Valley we have gone in the wrong direction. In the 1950s-70s, the Willamette Valley provided over 50% of its own food needs. Today, that number is less than 5%—an alarming decline caused by globalization and industrial food systems.

But this can change. Cascadia has the resources to feed itself—if we invest, as we must, in localized, regenerative agriculture.

How the Willamette Valley Can Lead the Way

To prevent the mistakes of California, we must focus on:

Regenerative farming – Moving away from petrochemical-based agriculture toward soil-building practices.

Seed sovereignty – Saving and cultivating regionally adapted seeds through community-based seed banks.

Perennial food systems – Developing food forests and polyculture systems to increase long-term resilience.

Water self-sufficiency – Using rainwater harvesting, swales, and greywater systems to reduce reliance on external water sources.

Local food networks – Strengthening farmers’ markets, CSAs, and cooperative distribution systems.

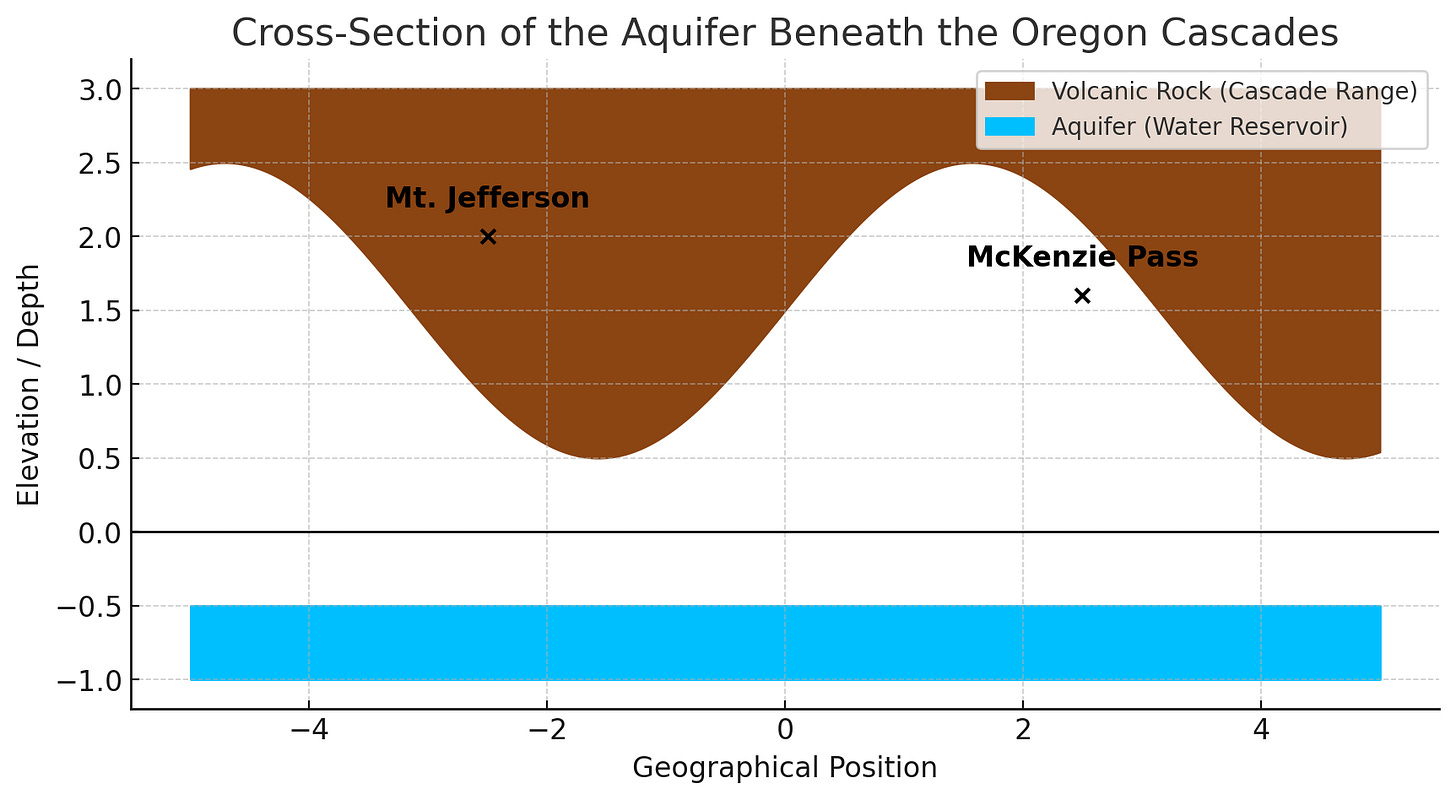

Recent research has unveiled a substantial aquifer beneath Oregon's Cascade Range, with significant implications for the Willamette Valley's water resources.

Discovery of the Cascade Range Aquifer:

Magnitude: A study led by the University of Oregon estimates that this aquifer holds at least 81 cubic kilometers of water, nearly three times the capacity of Lake Mead.

Location: The aquifer is situated beneath volcanic rocks at the crest of the central Oregon Cascades, particularly between Mount Jefferson and south of McKenzie Pass.

Formation and Function:

Geological Composition: The aquifer is formed within layers of porous volcanic rock, resulting from historical lava flows.

Recharge Process: It is primarily replenished by snowmelt and rainfall, with water percolating through the volcanic rock and taking approximately seven to ten years to emerge at springs.

Implications for the Willamette Valley:

Sustaining River Systems: The aquifer feeds into major rivers such as the McKenzie, Deschutes, and Upper Willamette through large-volume springs, ensuring steady river flows even during dry periods.

Water Resource Management: Understanding this aquifer enhances water resource planning for the Willamette Valley, supporting agricultural activities and urban water supplies.

Considerations:

Climate Change Impact: The aquifer's recharge depends on snowpack levels, which are projected to decrease due to climate change, potentially affecting the aquifer's sustainability.

4. A Call to Action: Building the Cascadia Food Guild

The Role of the Cascadia Seed & Food Guild

The Cascadia Seed Guild was founded on the principle that seed sovereignty is food sovereignty. Now, we are expanding this vision into the Cascadia Food Guild, focusing on:

🌱 Preserving and distributing heirloom seeds through decentralized seed banks and local seed suppliers.

🌱 Developing emergency food security projects, including community seed propagation centers.

🌱 Supporting permaculture-based food production in both urban and rural areas.

🌱 Creating cooperative models for food processing, storage, and distribution.

How You Can Get Involved

Start saving seeds—join a local seed swap or support regional seed banks.

Grow your own food—even small-scale gardening reduces dependence on industrial agriculture.

Support local farmers—buy from CSAs, farmers’ markets, and regenerative producers.

Advocate for local food policies—push for zoning laws that protect farmland and encourage local production.

Join the Cascadia Food Guild—help build a resilient, community-based food system.

5. Conclusion: A Defining Moment for Cascadia

California’s Central Valley is a warning sign—a region that once seemed invincible is now on the edge of collapse. We cannot afford to wait until crisis hits. The time to build a regional food system that is resilient, regenerative, and locally controlled is now.

The Willamette Valley has everything it needs to become a model for food sovereignty, but it will take community action and forward-thinking leadership to make it happen.

This is our moment. Let’s reclaim our food system—one seed, one farm, and one meal at a time.

🌱 Join us in building the Cascadia Food Guild.

Interesting post, I like that you have a call to action at the end. There is definitely a lot of interest in seed swaps and permaculture in the Willamette Valley, it would be interesting to have some sort of coalition develop where groups like the Agrarian Sharing Network and others that could facilitate something like a conference or knowledge and seed swap. I guess they already kind of do that with the propagation fairs. A cooperatively-owned food processing facility for small farmers is a good idea too. My family used to sell prunes to local driers but now they just rot on the trees.

I think that unfortunately, Oregon agriculture is already facing a lot of the same pressures that California agriculture does. This includes pressure from Urban Growth Boundaries, the need for more housing, data centers, and clean energy infrastructure, increasing summer temperatures, reduced water allotments (farmers do get their water shut off in Oregon), and an aging farmer population. Many industries, including the process green bean industry, which has been in the valley for over a hundred year, are declining. I expect that by the end of the 21st century, the Willamette Valley will be more similar to Medford as far as climate. The aquifer in the Cascades is interesting, maybe it will be developed someday. Hopefully it will still be in public hands after this corrupt shit-show of an administration is over. I wouldn't be surprised if they sold it off to some company or nation to pay for Bitcoins or tax cuts.

Processing tomatoes are a big crop in the central valley of California, but they are starting to move some of the production to eastern Washington and Oregon. Interestingly, Milton-Freewater was a big tomato producer in the early part of the 20th century. Looks like a lot of that industry might be coming back. I wonder what other crops will be heading this way as climate refugees.