GMO Emergence

Monsanto launched the first genetically modified organism (GMO) seeds in 1996. These were Roundup Ready soybeans, which were engineered to tolerate glyphosate, the active ingredient in Monsanto's herbicide; Roundup. This development marked a significant turning point in agriculture, leading to widespread adoption of GMO crops in the subsequent years.

Here, Bill Mollison speaks to the actions which relate to our next sections.

Monsanto was the first company to commercially launch GMO seeds with its Roundup Ready soybeans in 1996. However, other companies were involved in GMO research and development prior to that. Notable competitors like Calgene and Syngenta (under its predecessors) were active in genetic engineering around the same period.

Calgene, for instance, introduced the Flavr Savr tomato in 1994, which was the first genetically engineered food crop to be commercialized. The Flavr Savr tomato was engineered for delayed ripening but had limited commercial success. However, this was a food crop rather than a seed designed for large-scale agricultural systems like Monsanto's.

Bill Mollison Speaks Out On Seed Hijacking

Bill Mollison was the co-creator of #Permaculture along with David Holmgren, in Tasmania. Bill Mollison's assertion that chemical companies like Monsanto (now part of Bayer) engaged in acquiring major seed suppliers to monopolize seed supply chains. Over the decades, Monsanto and other agrochemical giants strategically bought seed companies, consolidating control over global seed markets. This practice raised concerns among farmers, environmentalists, and permaculture advocates about the erosion of seed diversity, farmer autonomy, and the centralization of agricultural power.

Key Evidence of Monsanto's Strategy:

Acquisition of Seed Companies:

Monsanto began purchasing seed companies in the 1980s and aggressively expanded its portfolio in the 1990s and 2000s.

By the 2010s, Monsanto had acquired over 40 seed companies, becoming the world’s largest seed supplier. This included companies producing conventional and genetically modified (GMO) seeds for staple crops like corn, soybeans, cotton, and vegetables.

Notable acquisitions included:

DeKalb Genetics Corporation (corn and soybean seeds) in 1998.

Seminis (vegetable and fruit seeds) in 2005, which controlled an estimated 40% of the U.S. vegetable seed market.

Delta and Pine Land Company (cotton seeds) in 2007.

Integration with Agrochemicals:

Monsanto's strategy involved pairing GMO seeds with its proprietary herbicides (like Roundup). Farmers who purchased Monsanto's Roundup Ready seeds were often required to buy the associated chemicals, creating a vertically integrated system.

This further consolidated control by tying seed usage to chemical inputs, reducing farmers’ choices. There is a video featuring Monsanto here.

Smaller, independent seed companies struggled to compete against Monsanto’s acquisitions and market domination, reducing the diversity of seed suppliers.

As a result, farmers increasingly depended on a few large companies for seeds.

Consolidation Across the Industry:

Other chemical companies, like Dow Chemical, DuPont (now Corteva), and Syngenta, followed similar acquisition strategies, consolidating the global seed market.

Today, four companies (Bayer/Monsanto, Corteva, Syngenta/ChemChina, and BASF) control more than 60% of the global seed market. This is an incredibly tenuous situation for us all to be in, so what are we able to do about it? More on this soon.

Criticisms and Implications:

Loss of Seed Diversity: Consolidation has led to a significant reduction in the genetic diversity of crops, making global agriculture more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and climate change.

Patent Enforcement: Monsanto’s aggressive use of seed patents often forced farmers to buy new seeds annually, rather than saving and replanting seeds as they traditionally had.

Monopoly Concerns: The control of seeds—the foundation of food production—by a handful of corporations has sparked debates about food sovereignty and corporate power over agriculture.

Bill Mollison’s concerns align with the permaculture principle of seed sovereignty, which emphasizes maintaining access to open-pollinated, non-patented seeds as a cornerstone of sustainable, resilient agriculture. The rise of seed libraries, heirloom seed networks, and farmer-led seed breeding initiatives has been a direct response to counteract these trends.

So What Can We Do?

Revoking patents on GMO seeds is a complex and challenging process due to legal, economic, and political factors. It would require significant shifts in policy and practice, as well as a rethinking of intellectual property (IP) laws. Below is an outline of the key challenges and possible pathways:

1. Challenges in Revoking Seed Patents

Legal Protections for Intellectual Property:

Patent Laws:

GMO seeds are patented under existing IP laws, which grant the patent holder exclusive rights to the invention for a specific period (usually 20 years).

Revoking these patents would require changes to national and international laws governing patents, such as the U.S. Patent Act and the global Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement.

Precedents:

Revoking patents could set a legal precedent that might deter future innovation in agriculture and biotechnology, leading to resistance from industry stakeholders.

Corporate Resistance:

Economic Power of Corporations:

Companies like Bayer/Monsanto, Corteva, and Syngenta have substantial financial and political influence. They would likely lobby against efforts to revoke patents.

Contracts and Licensing Agreements:

Farmers who use GMO seeds sign contracts prohibiting seed saving and mandating the purchase of new seeds each season. Revoking patents would disrupt these legal arrangements.

Global Trade Implications:

Patents are often tied to international trade agreements. Revoking seed patents could strain relations with trading partners and disrupt agricultural supply chains.

2. Pathways to Revoking or Reducing Seed Patent Dominance

Policy and Legislative Changes:

Government Intervention:

National governments could pass laws limiting or banning patents on living organisms, including seeds. For example, countries could follow India’s lead, where plant varieties cannot be patented, though they can be protected under the Plant Varieties and Farmers' Rights Act.

Compulsory Licensing:

Governments could issue compulsory licenses, forcing companies to allow others to produce and use patented seeds at lower costs while keeping the patent in place.

Legal Challenges:

Patent Invalidity:

Activists or organizations could challenge the validity of seed patents in court, arguing they fail to meet the legal requirements for patents (e.g., novelty, non-obviousness).

Morality Clauses:

Some jurisdictions allow for patent revocation on ethical grounds. Activists could argue that patenting seeds violates public interest, food sovereignty, or biodiversity principles.

Public Movements:

Pressure on Corporations:

Public campaigns could push corporations to release patents voluntarily, as was seen with COVID-19 vaccine IP debates.

Seed Sovereignty Movements:

Advocacy for open-source seeds and community seed banks could reduce reliance on patented seeds over time.

Alternative Innovations:

Open-Source Seed Initiatives:

Initiatives like the Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI) provide an alternative framework for sharing seeds without patents.

Heirloom and Landrace Revival:

Supporting traditional seed varieties and breeding programs can diminish reliance on GMO seeds.

3. Feasibility of Revoking Patents

While revoking patents outright is legally and politically difficult, the following approaches could chip away at their dominance:

Encouraging public and nonprofit organizations to develop and distribute open-access seeds.

Advocating for policy reforms that prioritize farmers' rights and biodiversity over corporate IP protections.

Creating incentives for companies to release patents once they expire (e.g., tax benefits or subsidies).

Conclusion

Revoking seed patents would require significant political will, legal changes, and public advocacy. While difficult, it’s not impossible—especially when aligned with broader movements for food sovereignty, sustainable agriculture, and biodiversity conservation. A combination of legislative reform, public pressure, and alternative seed systems is likely the most effective way forward.

Lets Create Decentralized-Distributed Seed Propagation

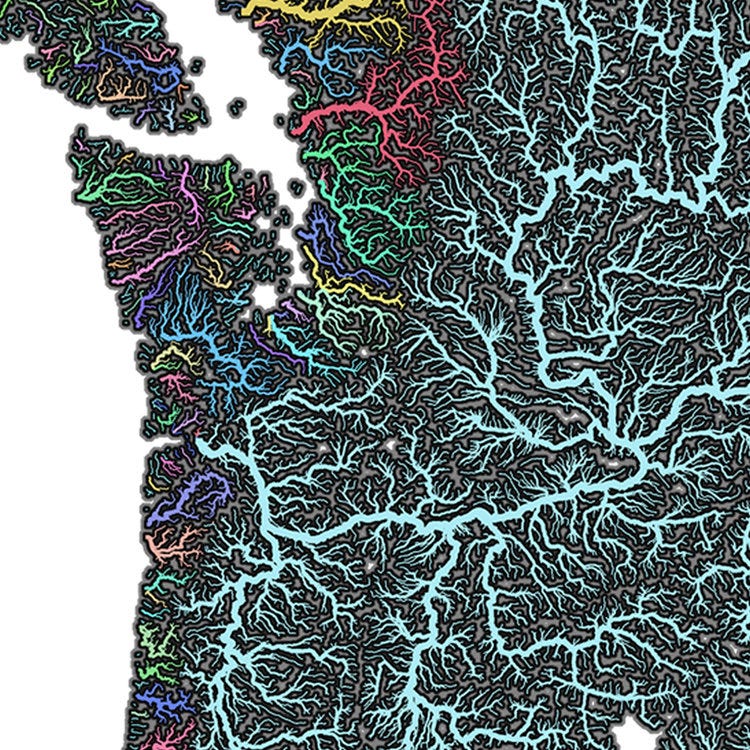

Let’s create decentralized-distributed seed propagation centres, far and wide. Here we created a fully developed plan for the Cascadia Bioregion of the USA. This is to bring resilience to the Pacific Northwest of the USA, which is under threat via the Cascadia Subduction Earthquake. “The purpose of these Emergency Seed Banks is to improve our resilience in the face of any challenges which we may encounter. As a note-point, there are 185 Bioregions on Earth in total, as defined here.”

We can accelerate our success rate by moving to growing landrace gardens all around our Country, well in fact, our World. Here, Joseph Lofthouse describes landrace seed evolution so succinctly: "A locally-adapted, genetically-diverse, promiscuously-pollinating food crop. Landraces are intimately connected to the land, ecosystem, farmer and community. Landraces offer food security through their ability to adapt to changing conditions." This is something the seed monopolies simply cannot do.

Once again, thank you for reading this, please stay tuned for our next article in our evolving series on the critical importance of seeds for all forms of land-based life forms. And best of all, save seeds.